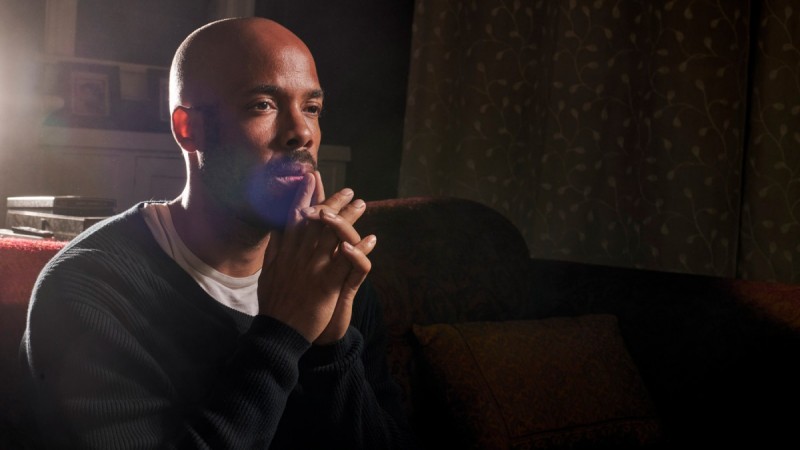

The Intruder ©Christopher Malcolm

Congratulations to Christopher Malcolm, one of three Best in Show winners of APA LA's Off the Clock 2021, juried by Rebecca Morse. Malcolm is an award-winning Los Angeles-based commercial photographer, director, and cinematographer with clients such as Nike, Lululemon, ASICS, and Verizon. His work has also appeared in Runner's World, Men's Journal, and Bicycling. He has won awards from a number of prestigious institutions, including PDN, APA, American Photography, IPA, and The Lucie Awards. He believes, "the primary role of an artist is to tell a story." During the pandemic, he spent time making self-portraits in a series entitled Quarantine Stories.

As a "people" photographer, how did it feel to turn the camera on yourself and be the subject? How long were you in lockdown before you came to the idea?

CM: Turning the camera on myself is oddly natural to me. Not, mind you, because I’ve ever had any illusions about being a “on-screen” personality myself. I am firmly a behind the scenes guy and very happy with that. But, over the years, I’ve ended up on camera enough as an actor or model to not be super uncomfortable on that side of things.

True, I usually am only in front of the camera for practice. Whatever “acting” I’ve done, if you can call it that, is largely aimed at making me a better filmmaker and photographer. It’s hard to know how to direct a subject if you don’t understand on a practical level what they are going through. So I’ve often thrown myself in front of the camera just to experience some of their discomfort as a way to make me better at speaking to my actual subjects when the time comes.

Also, as someone who considers lighting the main weapon of a photographer, I have a regular routine of doing lighting practice for a least an hour or so every day. Because I am a “people photographer” and I live alone, there is often little choice but to step in front of the camera during practice sessions. At the beginning of quarantine where it seemed as though we all might very well live the rest of our lives inside our houses, I had very little choice but to serve as my own model. If I go more than two weeks without creating something, I tend to get a bit depressed. So, it didn’t take long before the concept for the project came to me. It did, however, end up lasting much longer than I had planned as the pandemic continued on and on.

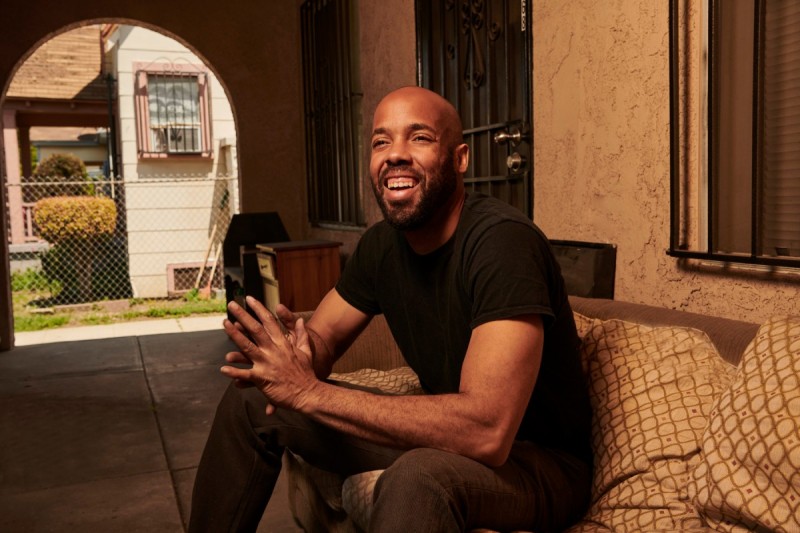

Self Portrait ©Christopher Malcolm

Did you feel awkward in front of the camera, or did you know exactly where you were going with Quarantine Stories?

CM: The only real objective I had with the series was to get better. Every day, like any day, is an opportunity to improve. So the only real goal I set for myself with each episode of the Quarantine Stories series was that I had to try something new. Or, at a bare minimum, improve on existing skills. The image which won Best in Show at the APA Off The Clock competition, for instance, was an excuse to practice color grading a scene through light. The color tones in the image are achieved entirely in-camera through the use of light, gels, reflections and so on. Nothing is added in post aside from me cleaning up a bit of dust on the hardwood floor. So my objective every day was simply to be a better photographer at the end of the day than I was at the beginning. The scope of the series is really a result of the length of the quarantine period and the need to come up with different approaches every single day.

There is a cinematic and narrative quality to the images. Did your background in film and screenwriting influence this project? Did any specific films influence you?

Everything I shoot, whether a personal project or a commercial assignment is driven by my love of cinema. So whether there is a video component to a project or not, my immediate references in life almost always relate in some way to any of the millions of frames that have passed by my eyes over the years as a cinephile. It’s hard to reference a specific film for The Intruder image specifically. It was more a matter of establishing a mood. The pools of light are reminiscent of something you would see John Alton do for film noir. But, I find myself more and more drawn to color. So I wanted to take that same mood and merge it with subtle blue-greens that you might see in a film like A.I. Artificial Intelligence which was shot by Janusz Kaminski for Steven Spielberg. But those are just visuals I would say that would play in the back of my mind rather than being lighting references that I was specifically going for.

That’s what film does. You create characters. Those characters motivations help steer the arc of your story. The cinematographer comes in and creates visuals which further enhance the emotion of each scene. This is further subsidized when the editor comes in and helps regulate the audience’s heartbeat. And the composer plays with the audience’s heartstrings. It’s a team effort with one goal. To translate an emotion to the audience.

As a photographer and actor (in a self portrait sense) for this series, I was in charge of both bringing the character to life on screen, but also compensating for my lack of actual acting ability by supplementing my own performance with light. It’s a way of bringing out a performance through light and color that is very useful even when you are working with a professional model who may just need a little bit of help visually to fully embody their character.

Top Gun Self Portrait ©Christopher Malcolm

Is this man a fictional character or parts of yourself? How do you see the viewer relating to him?

CM: Interesting question. I would say that every character I write is essentially an extension of myself. It’s not always clear to me at the time that this is what I am doing. But it’s always there. I began my creative career as a screenwriter. I’ve written dozens of scripts throughout the years. And looking back at them, it’s very easy to tell where I was emotionally at the time I wrote each one. I may not have been fully aware of what I was going through as I was first writing them. But, as the years pass and you have time to reflect, I can read those scripts, whether they be drama, comedy, or action, and see a very in depth portrait of myself at that point in my life.

Because Quarantine Stories was going to be a different episode each day, there was a demand to have variety. So it’s easy to think that some of it is just made up. But, I’d still venture to say that every episode is still a reflection on me. Perhaps even a more honest reflection than I was intending to offer.

But I think, again, this is the entire intention of art. I think great artists, and, by the way, I am not necessarily lumping myself into that category, but great artists or people who aspire to make great art are people who are not afraid to completely reveal themselves through art. They are open and willing to expose themselves and their emotions, dreams, and fears to an audience. And the art that breaks through is because viewers are able to see the difference between art as artifice and art as honesty. An audience can feel honesty. And when they sense that you are giving of yourself, it is human nature to want to connect with that art emotionally and relate it to your own experience.

Ford Escape ©Christopher Malcolm

The man in the photographs seems to be searching for a hero, a way to reframe his masculinity and existence. Is this a series that includes a personal search of self and identity?

CM: To a certain extent. I think the nature of the project, being conceived by me, shot by me, starring me, with me as my own primary audience. Haha. I think due simply to the objective of the project, to explore light and explore my depths as an artist, that you can’t help but to also explore the depths within yourself. An artist is his or her work to a certain degree. It’s not like a welder who creates widgets. No matter how good that welder is, that widget isn’t a definitive portrait of the welder as a human being. But I think as an image-maker and a story teller, the stories we tell reveal who we really are. What and who we consider to be physically attractive or artistically inspiring paints as much of a self portrait as an actual self portrait with ourselves as subjects. So, to that end, every portrait, whether I am in it or not, is essentially a search for self.

Some of the pictures are haunting and mysterious, as if something sinister is happening or about to happen. The images are hard to nail down. How did you approach this with such an open end to the narrative? Did you have a resolution in mind when you made the stories?

CM: The wonderful thing about doing still photography is that it inspires you to leave questions that linger. As a screenwriter, I need a beginning, middle and end. If I were telling the same story in a screenplay, I would have a full three act structure and a big finale that might reveal exactly what it is the man is searching for. But, because still photography is a single frame, or smaller collection of frames, rather than 24 frames per second, it lends itself to certain questions being unanswered. With a series like this, that can actually be more powerful because it can force a viewer to engage with their own imagination. Like a novel where the reader has to imagine what the lead character would look like in their minds. By leaving The Intruder episode open ended, it inspires an audience member to fill in the blanks. They have their own opinion on who the man is, what he’s looking for, what exactly is that light shining on. By inspiring your audience to engage in that way, the art itself can become more memorable.

Man in the Mirror ©Christopher Malcolm

Will you continue to work in self-portrait now that you can photograph people again? Do you plan to do more conceptual work in addition to your thriving commercial career?

CM: You know, it’s funny. I tend to do self portraits largely out of necessity. Like I said, I live alone, but I have an emotional need to create. So, if I have to create to keep my spirits up, and I’m the only subject available, well, I guess it’s time for another self portrait! With that said, oddly enough, I feel as though some of my best portrait work of the last several years has come in the form of self portraiture. I believe the reason for this is that, because self portraiture is devoid of a client or even a subject that you need to satisfy, there is more freedom. I don’t really care if I look good in a self portrait. I’m more interested in the process and the learning. Because of this, I can really explore artistically.

Yet, even though this is a freedom granted through practicing self portraiture, it does tend to find its way into my commercial work as well. Every trick I learn doing a self portrait series tends to eventually find it’s way onto set when I am working on client assignments as well. So, for me, self portraiture, even if inspired by necessity, ends up making me a better photographer in the long run because I am opening up creative avenues and learning technical craft that advances both my career and my understanding of self.

Where do you see this project living in the world?

CM: Honestly, I would love to see the Quarantine Stories series mounted as a physical exhibition once the world reopens and gallery openings start really revving up again. There are like thirty-something different episodes I did of the series, each telling a different tale. I can easily see an exhibition with the episodes separated out so that the entire show is a bit of a mystery box. Whether or not I’m prepared to see that many prints of myself blown up big on a wall at the same time or not is a whole different story. But as an artist, I think it could be really special.

Self Portrait ©Christopher Malcolm

Read his weekly column in FStoppers.com