Interview by Juliette Wolf-Robin

Todd Baxter takes a familiar subject matter and adds an element of the unbelievable.

© Aubrey Videtto. Todd Baxter APA Member since 2011.

Q. You originally started by teaching photography. Are there lessons that you would have taught differently knowing what you do now about the business?

“Teaching art” is a little bit of a misnomer. I was just focused on getting students making work, getting them creating because, really, that’s what being an artist is: making art. It’s simple, but it’s incredibly difficult for most people — even those who majored in the arts — to build a daily habit of making art once they’re working, building a family, or whatever it is they do all day. The reality is, most of us have to have a day job, and it’s tough to find time and energy at the end of a long day or on the weekends to feel and be creative.

I was lucky that my mentors in school had emphasized how hard it was going to be to keep making art after I got out of school and into the “real world.” I was braced for it, and I tried to pass that along to my students. It was probably a good reminder for me too. So I don't think I’d have changed too much about how I taught art, knowing what I know about the photo business (except for maybe how to use a digital camera, since that wasn’t a thing back then).

Q. How did working as an Art Director influence your career as a commercial photographer?

I probably wouldn’t have intentionally headed toward a career in commercial photography without my time working at ad agencies. I was able to see, to a certain extent, what was involved in conducting commercial photo shoots and then envision myself in the role of photographer. Having come from an art background, I had little practical knowledge of owning and operating a business — I had totally focused on the creative process. So the insight I gained working on creative teams opened up new possible career options I hadn’t considered before.

Conversely, now that I am working as a commercial photographer, the insight I have into the agency creative process is invaluable. A lot of people and a lot of work are involved in getting a concept to the stage of a photo shoot. Really understanding that the photo shoot is just one piece of the pie, I can better communicate and help problem solve with the creative team.

Q. Have your personal projects been picked up for commercial or editorial use? If so, what was an idea that you had that was then fit into someone else’s idea?

Yes, that’s happened quite a lot actually. A number of personal pieces have been licensed for editorial use in a variety of US and international publications. The instance I’m most proud of happened last year, when I teamed up with Ogilvy on a set of outdoor pieces for Camp Wandawega (“a summer camp for adults”).

Tereasa Surratt, Creative Director, Ogilvy, Chicago, got in touch about an idea they’d had to use a handful of images from my Owl Scouts series in the campaign, which played on the idea of the spooky, scary campfire stories we all love. Since several of the Scouts images are very dramatic, they wanted to use them with their copy to show these imaginings of camping gone terribly wrong. I loved the idea, so we worked together to select the images and finalize the copy.

The pieces were plastered on construction walls and buildings in alleys around Chicago, and they looked great. The crazy part was they ended up winning a Bronze Lion from the 2013 Cannes Lion Festival for Design/Photography. I was stunned. I knew I was really lucky to have the team appreciate the work for what it was and not want to alter it in any way, and they were adamant about giving me the creative direction credit on the Cannes entry, since I’d developed the Owl Scouts project prior to the campaign. I still can’t believe that happened. And I realize now I didn’t even tell many people about it at the time.

Q. Is there a word that people use to describe your work that you particularly like?

That’s a tough question. I hear (or read) people using words like “hyper-real,” “painterly,” “haunting,” “magical,” and I’m like, wait, people are writing about my work? That’s so rad!

I’ve had to get used to my work being described at all. Some descriptors help me understand how it’s being received, even if it’s not how I imagined it being interpreted. I really respect that each individual’s interpretation of art is completely legitimate. We all see things through the lens of our own experience. I feel that if someone has a reaction at all, they’ve at least taken the time to experience it.

If I had to choose one word, though, it would probably be something like “magical.” I love to create the unexpected but subtle sense that something is real that can’t be real — take a familiar subject matter and add an element of the unbelievable. It’s something I’ve been drawn to since I was a kid listening to creepy, magical fairy tales. And I’m still drawn to it as an adult in other artists’ work.

Q. Is it your personal or commercial work that has mostly led you in a certain direction?

I was drawing and painting, and I was working in advertising. And that’s when I decided to do photography, where I basically took the type of imagery I was making for my paintings and drawings, but applied commercial photography finishes. It made the images a little bit more graphic, or maybe “polished” is the right word. I was merging my fine art with a bit more of a commercial photography aesthetic. They definitely continue to inform each other.

Q. Have you spoken to any galleries about the Owl Scout project?

You know, I haven’t. Other than right after art school, I haven’t sought out any galleries. That’s not to say I wouldn’t be interested; I just haven’t cultivated those relationships. My connection to most of the venues where I’ve shown my work has been the result of personal connections and organic conversations about ideas for shows. Owl Scouts debuted in Indianapolis in 2010 at Mount Comfort (“a space for champions”), thanks to an interest by Casey Roberts, the owner. A storefront gallery and studio space, I don’t know that Mount Comfort would have been considered a traditional gallery at that time, but now the area is evolving into an arts district.

I’ve shown a lot at Lula Café in Chicago, which has been a fantastic venue for getting my work in front of a great audience. I don't know what it is about that place (other than their amazing food and steady supply of great art) that seems to make for such a good fit between my work and their patrons. I’m always overwhelmed by the supportive feedback I get when I show there.

The first Project Astoria show has recently been shipped back to LA from Chicago after its winter 2013 debut. Now that I have those giant pieces lying around with the Owl Scouts pieces, I’m starting to think I need to sucker a few galleries into showing my work so I won’t be tripping over them at home.

Q. Is Owl Scouts due to become a book?

I’ve batted that idea around with my friend Joe Meno, a Chicago novelist, and my wife Aubrey, a writer. But I’m leaning more toward some type of animation or movie project. Aubrey and I fleshed out a narrative on a road trip about a year back, and it’s been lingering in the back of my mind ever since. I’m starting to more seriously develop some film concepts, so as of right now that’s toward the top of the list.

Q. Do you find yourself pulled in any particular direction? Five years from now, would you like to be doing more commercial work or more gallery work?

For the first five years or so of owning a photo business, I really liked the balance I’d struck between the commercial and personal work. Commercial jobs took the pressure off the personal work — it was a relief not to have to rely on the personal work to make a living.

But now, having gotten a lot of positive feedback on projects like Owl Scouts and Project Astoria, I’m starting to feel more confident and maybe more ambitious in what I might want to do with the personal work. That said, the commercial work isn’t going anywhere (I hope!). Those jobs play a huge role in building relationships with other creative people and in the evolution of my creative process. Plus, I just like working. Photo jobs are fun — a HUGE amount of work, but really energizing and rewarding, too.

Q. Are there people that you collaborate with on a regular basis? Do you have a team?

I have a really good team — not necessarily fixed — that I work with for lots of commercial stuff and on the personal projects. Everyone has their strengths — some people are a better fit for some projects. And I also love the chance to collaborate with new people. It’s an amazing thing when I get to work with someone who brings a creative layer to a project I wasn’t expecting. Suddenly the whole thing is bigger and better than I originally imagined it. Or things I’d imagined come to life when I didn’t think that was possible.

In Chicago I worked with quite a few art students from SAIC and Columbia College who interned with me. They were like an army of awesome helpers. I hope that doesn’t sound at all demeaning because these students were a burst of amazing every time they showed up at the studio. And they kept me on my toes, thanks to their unending energy and sense of what was new and fresh in the art world.

I also have several friends and family members who are incredible artists with whom I collaborate whenever I get the chance. Among them is my wife, Aubrey, whose writing skills totally intimidated me when I read some of her work before our first match.com date. Anders Nilsen, Joe Meno, Kim Baxter, and Sage Reed are also among the super talented people I’m lucky to have in my inner circle. And I’m always meeting art directors, creative directors, and stylists on jobs who I get so excited to work with — right away, we’ll say to each other “Let’s get together after this and make something together!”

Q. There is a lot of finish work (retouching) of your images. Do you do it all yourself, do you do some of it, or do you have a go-to person?

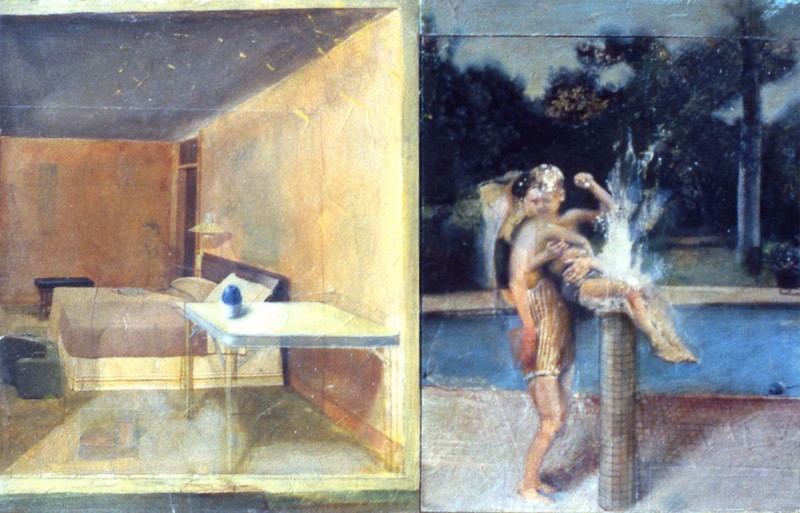

Up to this point, I’ve done almost all of my own retouching because for a long time, the retouching stage was an integral part of a “Todd Baxter” image coming together (for lack of a better way to put it). A lot of my process early on was based on my background in collage painting.

In case you’re not familiar with what that style of painting entails, here’s a quick overview: I would take a flat panel or board and gesso it (create a smooth white plaster-like surface as the base). Then I would take collage elements that I’d cut from books or magazines and glue them onto the panel. I would paint an acrylic varnish over that. Once it was dry, I’d use oil paints to match and weave the photo elements together, ultimately creating a single image that was somewhere between photography and traditional painting in appearance.

As my primary medium for several years in art school, that was still the go-to process my brain would switch to when making an image. That meant I usually set myself up for a lot of post-production Photoshop compositing. I’d see that phase as just as much, or even more, a part of the creative process as the photo shoot itself. This made it really hard to trust someone else to have the same vision I had for the finished piece. It was kind of too much to ask. The only person who’s been able to help much is my wife, Aubrey, who has become a self-taught retoucher just to assist me with my work when no one else can.

But as my photo creation process has evolved, I’ve learned that sometimes I’m making things too hard on myself by doing it this way. Now, I work more to get a lot of the world in camera in single frames. This makes it possible to finally start collaborating with outside retouchers; I’m just now starting to build those relationships. And as I do, I’m blown away by the level of artistry out there in the retouching industry. I really look forward to future collaborations with retouchers I’ve been talking to.

But especially with my personal work, there will probably always be lots of compositing I do myself. Sometimes, it’s just necessary because the world can’t exist in real life in a single frame, like most of the images in Project Astoria: Test 01, a multi-series photo project I’m creating in installments. Its story takes place in an alternate timeline with architecture, animals, and landscapes that don’t actually exist. I’d need an unrealistic amount of money to create these things in real life or to pay a retouching company to make them. And I’m not sure I would even want to. It’s pretty fantastic to have the kind of creative control I do to make alterations during post-production.

Q. Do you find that clients have an understanding these days of how much that “extra” work costs and the time it takes to complete?

It does seem more clients have realized how much the retouching stage allows for unlimited possibilities, which isn’t a bad thing. But not all clients realize that these possibilities aren’t always within the scope of their budget or their timeline for delivering final art. It’s an ongoing process to educate and communicate with clients so that everyone’s expectations are aligned. The last thing I want is to have to say “No, we can’t do that in this time frame,” or “That really isn’t something your budget can bear.” In fact, I’ve never said those things because I can’t say “no” to anything, which is why my amazing agent, Nell Murray, and Studio Manager/Executive Producer/Wife, Aubrey Videtto, are the ones on the front lines of post-production scope-creep. When things get hairy, their project management skills are essential.

In the end, no job feels like a success if the agency and client aren’t head over heels for the work and what they got for their money. But it’s also critical how everyone feels it’s going along the way to those final deliverables. I’ve delivered beautiful images in tight timelines, with tight-budget productions, that were recognized across the industry as successful. But because of a moment or two of confusion or misaligned expectations during post-production, I’m left feeling discouraged that the job might have been considered a failure in the eyes of the agency or the client.

Maybe it’s not so business-savvy to admit things aren’t always smooth as butter. But whether we all say it or not, this industry is in constant flux thanks to evolving technology and a tough economy. I take every challenge in a job seriously and use it as a way to improve my business and my process. After every job, Nell, Aubrey, and I sit down and regroup. We look at each stage of the job from the bid to uploading the final images, and we talk about how it’s going to go even better the next time. Our main goal is to avoid any confusion or predicament where the agency or client’s expectations are at odds with the scope of the job (either in production or post-production). I feel very confident now going into a new job, knowing we have a lot of strategies for communication and knowing the possible stumbling points we might face along the way.

Q. Children often appear in your images. There is a lot of playfulness. Has that been intentional or did one project just lead to another like that?

In my personal work I tap into a lot of childhood memories. So putting kids in the images/stories seems natural to me. And because I like dark fairy tales and children’s stories, I had a lot of kids in my drawings and paintings. But they didn’t really reappear until Owl Scouts. And that series ended up being a great way for me to connect with a lot of creative folks at agencies. So, inadvertently, many of the commercial projects to follow were more kid-focused. I love working with kids.

Q. How have you been able to navigate editorial, advertising, and fine art? Typically photographers focus their efforts in one area.

I’ve been really lucky. There were people in Chicago who nurtured me during my early years building the business, and I’m forever in their debt. They pointed out how much more engaged they were with pieces in my book that were part of personal artistic projects.

I’d had this idea early on that I needed to have a bunch of “commercial looking” work in my book in order to sell myself as a commercial photographer. But what I quickly learned was that art buyers and agency creatives were much more likely to connect with my fine art work because it revealed my creative process and how I might be able to contribute to their team.

That said, being a photographer who does a little of everything has also created something of an identity crisis. It’s a lot easier for someone to find you if you fit neatly into a category or two. And I’ve had a hard time doing that. I have work in my portfolio made via general advertising campaigns with big-name brands, but I have just as many pieces from healthcare campaigns, editorial work, and my fine art projects. It drives my agent crazy. It would be much easier to sell me to agencies if Todd Baxter = fill in the blank. But I don’t. Or maybe it’s just that my work doesn't fit neatly into a dropdown menu. It’s certainly possible that as I continue to evolve I’ll end up more in one category than another. In the meantime, I feel confident I can tackle whatever comes my way.

Thus far, the variety of jobs I’ve worked on has given me insight into successfully navigating different parts of the industry. For instance, a global healthcare campaign and a global retail campaign, though similar in many ways in the production process, are vastly different in other ways. Minute details can influence FDA approval of a campaign image that might only be meant for trade use with doctors. And a cute animal featured in an ad for kids’ accessories might be widely enjoyed plastered to the side of a building in one country but considered offensive in another. It’s helpful to have a broad knowledge base about the industry-specific considerations that affect creative decisions along the way. I find it lets me have a more nuanced relationship with the creative and account teams I partner with.

Q. When you talk about your work, what do you like to focus on?

Craftsmanship.

I don’t know if that’s the perfect word, but I’d really like to be seen as someone who respects his craft. I had a professor in art school who said ideas are a dime a dozen. He suggested not focusing so much on the idea, and instead focusing on the pursuit of the craft. His theory was that there are a lot of people out there looking for the next clever idea but that few people were taking the time to learn and practice their craft.

I really took that to heart. I’d like to think I have a lot of clever ideas, and sometimes they come in handy. But I’ve put my energy into being thoughtful and attentive to the details of my images — to treat each one, as much as possible, to the level of thoughtfulness a poet might use in the choice of every word in a poem. After all, I’m creating something that, by making it public, I’m asking people to give their time and attention to. Out of respect for that and for the medium, I pay attention to every detail — light, color, texture. Nothing is filler. And I sincerely hope that in this process I might convey something about myself, or my view of the world, or ideas that I’ve had, and that my audience may learn or feel or know something important to themselves in return.

Q. You’ve lived in a few locations. Do you think location has any bearing on the type of work you get?

Location is an important component to the work I get, but not the only component. I built my business in Chicago, and so many of my working relationships are there. It was a bit of a risk to move the studio across the country last year to Los Angeles. But with my agent in New York, connections in the mid-west, and now my studio in Los Angeles, I’d like to think I’m building relationships across the country. I try to connect with people wherever I go, and so does my agent. I recently had an old colleague write and ask if I’d be interested in working with a European agency he’s freelancing for. Yes!

Q. Any tips for an emerging photographer?

When I was still in advertising, a friend knew I was interested in changing careers and starting a photo business, so she got me in touch with a photographer she’d worked with. I called him and asked for advice, explaining I wanted to start doing photography on my own. He was very discouraging — going on about how bad the business was and how bad the pay is, and how little work there is. And I thought f*ck you. I’m going to do it anyway.

It wasn’t what I wanted to hear. And I wouldn’t want to do the same thing to someone else. My view of the business is totally different than that guy I talked to years ago, but it’s still a view that’s possibly in conflict with what an emerging photographer would want to hear.

But if you’re still reading, here’s my best advice: Build a portfolio of work that you care about, not what you think you “should” have in your book; take a business class or two in accounting and finance if you can; intern with a photographer who will let you see the business side of things; and make relationships with working photographers and agency professionals willing to act as mentors and answer industry questions as they come up. Be prepared to work really hard.

.png)